On Selectivity vs Influence: Ezra Pound

Can one practice selectivity when life is all about influence?

As I work on a story or an essay, I sit down knowing that the time is right to begin writing again. But the gravitational force of whatever books or films I have encountered will undoubtedly pull ideas towards them, influence them like the stars of old. Recent journal entries of reading and viewing could be flipped through like a horoscope, predicting events or at least sensing the infusions of other artists throughout the prose. This isn’t a writing process, it’s a half-disciplined consequence of living with art and literature and film while also creating one’s own works. And I don’t mind, but it’s a little less selective than I’d sometimes like it to be. To whit:

Ezra Pound was more selective. He had to be. All of his essays on literature and poetry demanded extreme selectivity of his own thoughts—though his style feels as if it was written in one lightning draft then sent on to the printer—and because of his mental selectivity, poets or statesmen or events couldn’t simply influence his work in the Cantos, they had to become part of it, or remain outside of it.

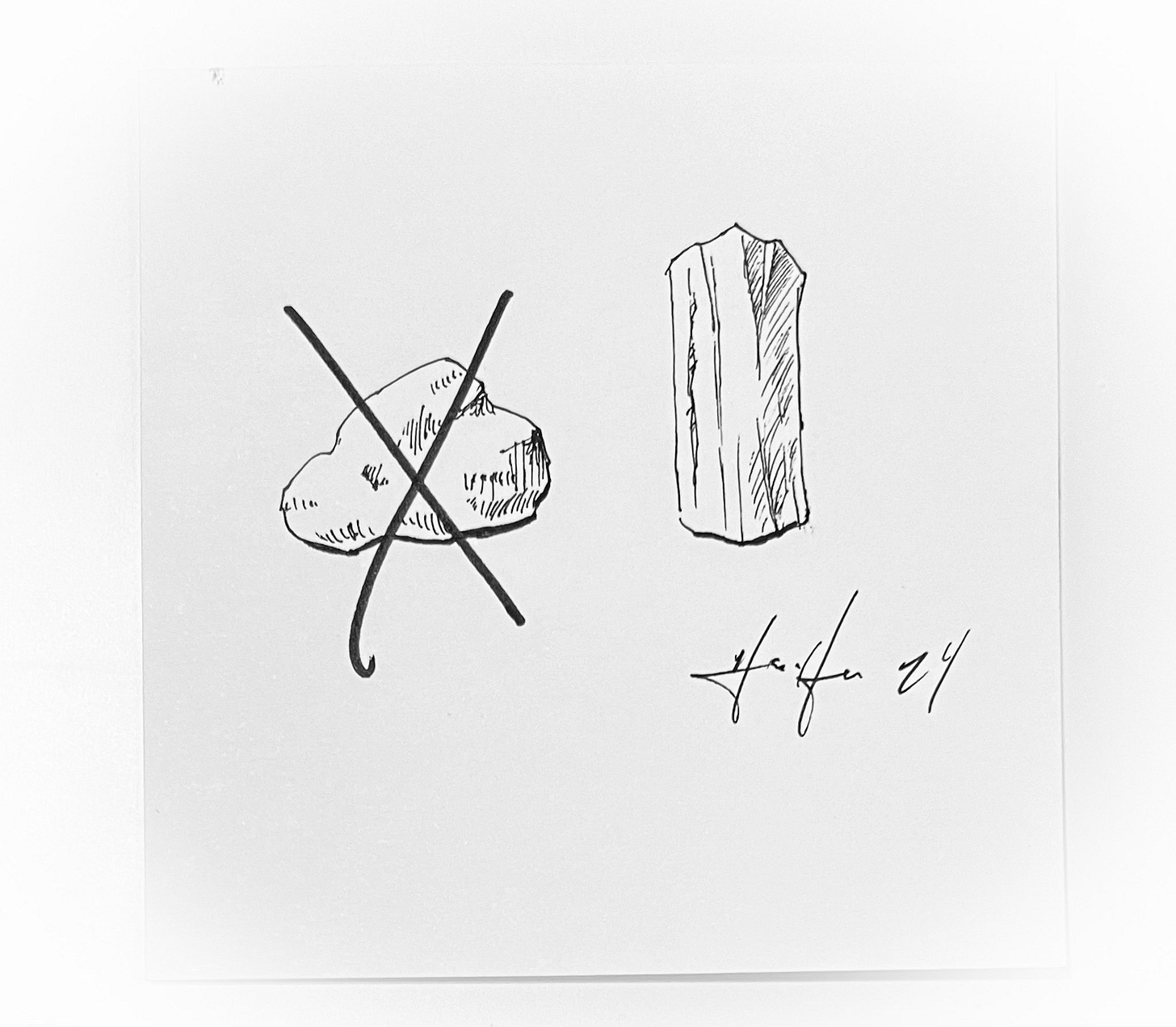

“The material one wants to fit in doesn’t always work. If the stone isn’t hard enough to maintain the form, it has to go out.” Pound, to an interviewer in the Paris Review Writers on Writing, volume 2, page 39.

Pound scoured his encounters with literature, poetry, history, and economics in order to examine the stone prior to using it in his structures.

So Pound’s statement that he dispenses with historical figures whom he wanted to include in the Cantos because"he doesn't fit the form, doesn't embody a value needed," (39) is a level of certainty I hadn’t even considered having until working on a book last summer. As I prepared my outlines and characters, I gathered seven or eight books that I knew I would carry throughout the writing of the novel. These hard materials became part of the foundation, firm and solid, rather than ephemeral, tangential, and meaningless.1

Still, Pound’s is a curious practice, almost mercenary, using historical figures the way one might use a friend until one is done with that friend.

One of those books, Mrs. Dalloway, ended up not working, and though one of the best books I read in 2023, did not get placed in the foundation of my own book, save four paragraphs which, when they were finished, carried about them a very faint smell of Woolf’s masterpiece.

Postscript: Pound on the real American form: “I’ll tell you a thing that I think is an American form, and that is the Jamesian parenthesis. You realize that the person you are talking to hasn’t got the different steps, and you go back over them. In fact the Jamesian parenthesis has immensely increased now. That I think is something that is definitely American. The struggle that one has when one meets another man who has had a lot of experience to find the point where the two experiences touch, so that he really knows what you are talking about.” (Ezra Pound, Pound, to an interviewer in the Paris Review Writers on Writing, volume 2, p. 41)